Your work has transformed rural healthcare in India. What inspired you to focus on community-based healthcare, particularly in tribal regions like Gadchiroli, and what were the defining moments that shaped your journey?

There are several factors which shaped my decisions, but since you asked for defining moments, I will touch upon a few. I was born and raised in Mahatma Gandhi’s ashram in Wardha. My father was a freedom fighter, and Gandhiji personally advised him to live in villages. This became part of our family legacy—to work for rural India.

As a child, I accompanied Vinoba Bhave in the Bhoodan movement, visiting many villages in Wardha. I saw first-hand the poverty, starvation, and hardships of rural life in the 1950s and 60s.

I remember that once in 1963, when I was 13 years old, my elder brother, Ashok, who was three years older, and I were riding our bicycles in the hot summer. We stopped to catch our breath, and he said, “Abhay, we are grown up; let’s decide—what will we do in life?” Both of us looked around and reflected on the dominant problems—poor agriculture, inadequate healthcare. Ashok then declared, “I shall improve the agriculture of rural India.” By default, without thinking much, I said, “Okay, then I shall improve the health of rural India.”

That was the moment we made our tryst with destiny—a commitment made at the age of 13, without fully realising its gravity. But growing up in Gandhi’s ashram, seeing our parents lead a different kind of life, and interacting with leaders like Vinoba Bhave had deeply influenced us. That was my first defining moment: my decision to improve rural healthcare.

The second defining moment was when I met Rani, my wife. We were classmates in medical college, completed our MDs at Nagpur Medical College, and started working in villages in 1978. However, we soon realised that our medical training focused on treating individual patients—clinical medicine, one patient at a time. But the real issues were at the community level.

To address this, we decided to go to the U.S. to formally study public health and research at Johns Hopkins University. When we returned in 1986, we were faced with the big question: What next?

We were clear we would not go to places with facilities because places with facilities don’t need you. We wanted to go to a place full of problems because no one wants to go there. That’s how we narrowed in on a semi-tribal district, Gadchiroli, about 1000 km from Mumbai, which was considered to be the kalapani of health services in Maharashtra.

It had poor healthcare, high infant and maternal mortality, and limited access to doctors. Thus in 1986, we moved to Gadchiroli; we were not God’s gift to the district; Gadchiroli was God’s gift to us because it gave us the opportunity to bring healthcare to the people who needed it the most.

Today I realise that our decision to work in rural healthcare was shaped by a series of defining experiences—my childhood exposure to rural hardships, our realisation that healthcare had to go beyond individual treatment, and our final decision to serve in one of India’s most neglected regions. What began as a childhood promise turned into a lifelong mission, proving that the dreams of a 13-year-old can indeed transform lives.

You have often spoken about Arogya-Swaraj—people’s health in people’s empowered hands. Based on your journey and experiences, how close are we to achieving this vision?

I have coined the vision of Aarogya Swaraj, borrowing from Mahatma Gandhi’s concept of Gram Swaraj. Gandhi believed that each village community should be self-reliant, self-sufficient, and independent. How could this be applied to health and healthcare?

The Sanskrit word for health is ‘swasthya’; this compound word basically defines good health as being a state where one transcends dependence on others for one’s wellbeing. In contrast, someone whose well-being is dependent on others is ‘a-swastha’ or unwell. Inspired by this idea, I coined the term Aarogya Swaraj, meaning a healthcare system where individuals and communities are empowered to take charge of their own health.

How close are we to achieving Aarogya Swaraj? We are miles away, yet a few inches closer to the dream. Several societal changes have contributed. Over the past 30 years, poverty has reduced, literacy has increased, and people are more aware of their health needs. Today they understand their health better and are more capable of taking care of themselves. We are also seeing community-driven healthcare innovations such as the Home-Based Newborn Care (HBNC) and ASHA Program to make basic healthcare accessible at home rather than requiring hospitalisation. These small but significant steps are moving us closer to the vision of Aarogya Swaraj.

While Indian society is becoming more capable of Aarogya Swaraj, our medical system is moving in the opposite direction. Healthcare is becoming more about sickness management than health promotion. High-tech hospitals and medical insurance systems encourage dependence rather than self-reliance. The current model promotes hedonism—enjoy life, fall sick, and rely on expensive medical care and insurance. Both hospitals and insurance companies profit when people get sick, rather than when they stay healthy.

This contradicts the very essence of Aarogya Swaraj, which emphasises preventive health, community self-reliance, and reducing dependency on high-cost medical interventions. If we truly want to achieve Aarogya Swaraj, we need to shift focus from sickness management to health empowerment, ensuring that people take charge of their own well-being rather than depending on a system that benefits from illness.

How can we effectively leverage technology and innovation to bridge the widening urban-rural healthcare gap in India over the next 25 years?

Technology is often equated with information technology or digital advancements, but in reality, it is a broad concept. One of the key aspects that differentiates humans from animals and plants is the ability to invent and apply technology. Simplifying technology and making it accessible to those who need it most is crucial for societal progress, especially in healthcare.

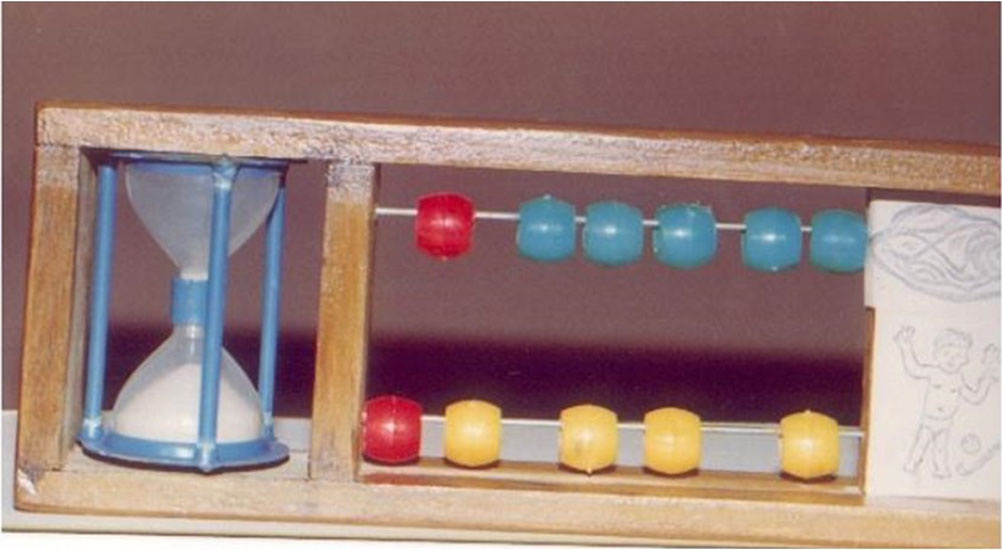

One example of technology adapted for rural healthcare is the Breath Counter, a simple device designed to help diagnose childhood pneumonia in villages. Pneumonia was once a leading cause of child mortality, with nearly 5 million deaths occurring globally. Though antibiotics existed, they often did not reach rural areas where children needed them most due to the lack of doctors and paediatricians.

The Breath Counter is designed to help illiterate community health workers or mothers diagnose pneumonia based on a child’s respiratory rate. The device consists of a one-minute sand timer, two rows of beads corresponding to different age groups—newborns and infants—and a simple counting mechanism, where every 10 breaths correspond to moving one bead.

This method allows rural women, even those with limited numeracy skills, to detect pneumonia without needing to count beyond 10. If the red bead is moved before the sand passes, it indicates pneumonia. When tested on 50 children, this method had an 82% accuracy rate, matching doctor diagnoses.

Breath Counter

This innovation illustrates how technology can be simplified to empower rural communities, reducing dependency on hospitals and making essential healthcare more accessible—aligning with the philosophy of Aarogya Swaraj.

Technology can also play a very powerful role in shaping the future of healthcare. Mobile phones, for example, have become ubiquitous, even in rural areas. It is a matter of time before real-time monitoring of blood pressure, blood sugar, and heart rate will make non-communicable disease diagnosis and management much easier.

Artificial Intelligence (AI) is also set to revolutionise diagnosis and access. AI advancements will revolutionise healthcare access, reducing dependence on doctors. ChatGPT and similar AI models have already passed medical licensing exams, demonstrating their ability to provide 24/7 medical guidance. However, while AI can diagnose and provide health recommendations, the responsibility of lifestyle changes still rests with individuals.

Advent in genomics will influence personalised healthcare. Future advancements in genomic analysis will allow individuals to predict disease risks based on their genetic makeup. This will enable early preventive actions, making healthcare more proactive rather than reactive.

Technology has the potential to transform healthcare into a wellness-driven model rather than a sickness-based industry. However, medical professionals and the healthcare industry must align with technological advancements to empower individuals with self-care tools, promote wellness rather than merely treating diseases and prevent the commercialisation of sickness and unnecessary medical interventions. By integrating technology with healthcare in an ethical and people-centric way, we can ensure that healthcare becomes more accessible, preventive, and empowering for all.

How do you envision scaling up your efforts across India, and what kind of support would be required from the government or the corporate sector to accelerate this impact?

Three key factors can be instrumental in accelerating scale-up.

First, the power of knowledge in driving change. In 1987, we conducted a study in two villages of Gadchiroli; it revealed that 92% of women had some form of gynaecology-related disease. This was published in The Lancet and highlighted the need for comprehensive reproductive healthcare beyond just family planning and safe maternity. The evidence influenced global health policies, shifting the focus from contraception to overall reproductive health. This demonstrates how knowledge, even from small-scale studies, can have a global impact.

The second factor that encourages scaling up is the government and institutional adoption for large-scale implementation. Our innovations, such as home-based newborn care and pneumonia management, were first tested in rural India and later validated through research. When the Indian government recognised their effectiveness, these approaches were integrated into national health programmes, leading to the training of one million ASHAs (Accredited Social Health Activists). Last year, these ASHAs provided home-based newborn care to 15 million rural neonates. The adoption of such innovations by governments and global organisations ensures large-scale impact.

The third factor that can considerably impact scaling up is policy-level interventions for sustainable health improvements. While governments play a crucial role in public health, some policies, such as generating revenue from alcohol and tobacco taxation, contradict health commitments. Alcohol, recognised as a leading cause of death and disability, continues to be a major source of state income. Governments must shift focus from revenue generation through harmful substances to investing in public health. Policy reforms in areas like air pollution, processed food regulation, and water supply can significantly enhance health outcomes.

One also needs a shift in the way corporates look at their corporate social responsibility. Management thinkers like Charles Handy and Michael Porter have emphasised the need for capitalism to have a social purpose. Capitalism possesses effective methods but lacks a unifying vision for societal well-being. As a result, there is growing recognition of capitalism with social values, where businesses integrate Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) beyond philanthropy—ensuring ethical sourcing, environmental sustainability, and consumer well-being.

The medical industry must expand beyond hospitals, pharmaceuticals, and diagnostics to focus on health promotion and disease prevention. A true healthcare system should prioritise wellness over merely treating illness. This shift would mean developing products and services that promote a healthy lifestyle, preventive care, and holistic well-being—making health promotion a sustainable, self-financed industry.

Scaling up healthcare innovations requires knowledge-driven change, government adoption, and policy reforms. Additionally, businesses must align their strategies with social goals, transforming the current sickness industry into a wellness industry. By doing so, we can create a healthier future where technology, policy, and enterprise work together to empower individuals and communities.

“One also needs a shift in the way corporates look at their corporate social responsibility. Management thinkers like Charles Handy and Michael Porter have emphasised the need for capitalism to have a social purpose.”

As we move towards India@100, what are the key healthcare challenges and opportunities you foresee, and what systemic changes are needed to ensure quality healthcare is accessible and affordable for all by 2047?

As India approaches its centenary of freedom in 2047, the country faces significant healthcare challenges that require urgent attention and systemic transformation.

One of the most pressing issues is ensuring equitable access to healthcare, particularly for marginalised communities such as the 11 crore tribal population who fare the worst in terms of health indicators and access to care. Without focused interventions, these communities will continue to be left behind in India’s development journey.

Another major challenge is the rising burden of non-communicable diseases (NCDs), including hypertension, diabetes, heart disease, stroke and cancer. As India undergoes an epidemiological transition, these chronic conditions are becoming more prevalent, demanding lifelong management with no permanent cure. Additionally, mental health concerns are escalating, with increasing cases of anxiety, depression, and psychiatric disorders. The lack of awareness, social stigma, and a shortage of mental health professionals further exacerbate the crisis.

Despite these challenges, India has significant opportunities to transform its healthcare system. Strengthening community health networks is a crucial step, with ASHA (Accredited Social Health Activist) workers playing a pivotal role in rural healthcare delivery. Expanding this model by introducing a male community health worker, “ASHOK,” will ensure better outreach and holistic care.

Community health worker measuring temperature of baby

Technology will also be a game-changer, with telemedicine, digital health platforms, and mobile-based healthcare solutions improving access to early diagnostics, remote consultations, and preventive care. Government policies must also focus on preventive healthcare by regulating the consumption of processed foods, trans fats, tobacco, and alcohol, all of which contribute to the growing NCD crisis. Implementing warning labels on alcohol, stricter food regulations, and clean air policies will be essential to improving public health outcomes.

To achieve quality, affordable, and accessible healthcare for all by 2047, systemic changes are necessary. Expanding and continuously upskilling the healthcare workforce, particularly ASHAs and ASHOKs, will enhance last-mile healthcare delivery. Strengthening public health infrastructure by investing in rural healthcare centres, telemedicine networks, and diagnostic facilities will improve accessibility. Promoting preventive healthcare through awareness campaigns on lifestyle diseases, mental health, and nutrition will help reduce long-term healthcare costs. Adopting technology-driven healthcare models such as AI-powered diagnostics, wearable health monitoring devices, and digital health records will revolutionise healthcare delivery.

Additionally, stricter regulations on harmful products like tobacco, alcohol, and ultra-processed foods will be vital in ensuring a healthier future. By implementing these strategic changes, India can build a robust and inclusive healthcare system, ensuring that by 2047, every citizen has access to quality and affordable healthcare, ultimately fostering a healthier and more resilient nation.

What message would you like to leave for the next generation of healthcare changemakers working toward this goal?

As India moves towards its centenary in 2047, healthcare must remain fundamentally driven by compassion, as it is ultimately about reducing human suffering. Inspired by Mahatma Gandhi’s talisman, we should constantly ask ourselves: will our next step in healthcare benefit the most vulnerable? True progress lies in ensuring that our health initiatives prioritise those who need them the most, rather than catering to those already well-served.

A critical shift is needed in how we view healthcare—not as a system that creates dependency, but as one that empowers individuals and communities to take charge of their own well-being. The essence of “Swasthya” (health) is self-reliance, and health programmes should aim to foster “Arogya Swaraj”—people’s health in people’s hands. Science and technology can be powerful enablers in this journey, bridging gaps in access and delivering solutions to those in remote and underserved areas.

To achieve healthcare for all, we must challenge conventional pathways. True change happens when we go where the problems exist, not where the facilities already are. It is in these difficult, underserved regions that healthcare professionals and changemakers can make the most profound impact. By focusing on strengthening primary healthcare, investing in grassroots health workers, and leveraging technology to improve accessibility, we can work towards a future where quality healthcare is a right, not a privilege.

Rather than offering a definitive roadmap, the goal should be to continually reflect and adapt, always ensuring that our efforts align with the needs of those who are most vulnerable. If we keep compassion and equity at the heart of our healthcare decisions, we can move towards an India@100 that truly embodies health and dignity for all.